Scraping the web

School of Data is re-publishing Noah Veltman‘s Learning Lunches, a series of tutorials that demystify technical subjects relevant to the data journalism newsroom.

This Learning Lunch is about web scraping: automatically extracting data from web pages.

Web scraping refers to the practice of writing code that will load a web page in order to extract some information from it automatically. It’s like a Roomba for the web.

Let’s say you wanted to save information about every US federal law with a certain keyword in it. You might have to get it directly from search results in THOMAS. If there are three results, you could just manually copy and paste the information into a spreadsheet. If there are three thousand results, you probably don’t want to do that. Enter the scraper. If you specify exactly what a law looks like in a page of search results, you can then tell the scraper to save every one it finds into a text file or a database or something like that. You also teach it how to advance to the next page, so that even though only ten results are displayed per page, it can cycle through all of them.

When is a scraper useful?

Information you can scrape is virtually always information you can get by hand if you want. It’s the same data that gets returned when a human being loads the page. The reason to create a web scraper is to save yourself time, or create an autopilot that can keep scraping while you’re not around. If you need to get a lot of data, get data at an automatic interval, or get data at specific arbitrary times, you want to write code that uses an API or a scraper. An API is usually preferable if it supplies the data you want; a scraper is the fallback option for when an API isn’t available or when it doesn’t supply the data you want. An API is a key; a scraper is a crowbar.

See also: Web APIs

What’s hard to scrape?

The best way to understand how a scraper thinks might be to think about what kinds of data are hard to scrape.

Inconsistent data

When it comes to writing a scraper, the name of the game is consistency. You’re going to be writing a code that tells the scraper to find a particular kind of information over and over. The first step is detective work. You look at an example page you want to scrape, and probably view the page source, and try to figure out the pattern that describes all of the bits of content you want and nothing else. You don’t want false positives, where your scraper sees junk and thinks it’s what you wanted because your instructions were too broad; you also don’t want false negatives, where your scraper skips data you wanted because your instructions were too narrow. Figuring out that sweet spot is the essence of scraping.

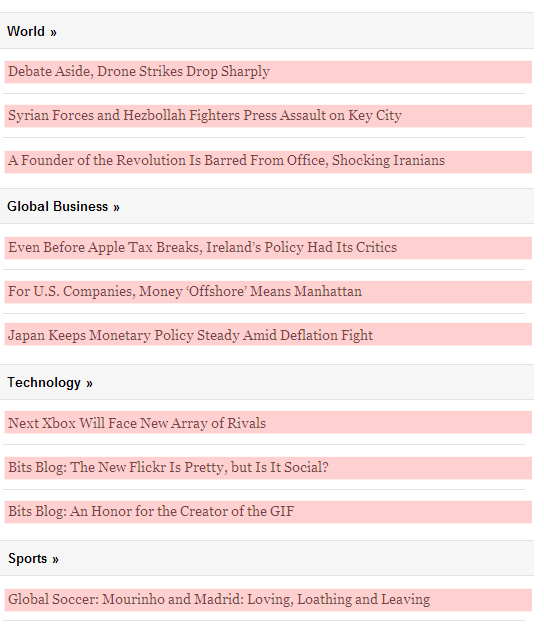

Consider trying to scrape all of the headlines from the New York Times desktop site, excluding video and opinion content. The headlines aren’t displayed in the most consistent way, which may make for a better reading experience, but makes it harder to deduce the perfect pattern for scraping:

On the other hand, if you looked at the New York Times mobile site, you’d have a comparatively easier time of the same task, because the headlines are displayed with rigid consistency:

Generally speaking, there are two big tools in the scraper toolbox for how you give a scraper its instructions:

The DOM

A web page is generally made up of nested HTML tags. Think of a family tree, or a phylogenetic tree. We call this tree the DOM.

For example, a table is an element with rows inside of it, and those rows are elements with cells inside of them, and then those cells are elements with text inside them. You might have a table of countries and populations, like this.

<table> The whole table

<tr>

<td>COUNTRY NAME</td>

<td>POPULATION</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>United States</td>

<td>313 million</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Canada</td>

<td>34 million</td>

</tr>

</table>

You will often have the scraper “traverse” this in some fashion. Let’s say you want all the country names in this table. You might tell the scraper, “find the table, and get the data from the first cell in each row.” Easy enough, right? But wait. What about the header row? You don’t want to save “COUNTRY NAME” as a country, right? And what if there is more than one table on the page? Just because you only see one table doesn’t mean there aren’t others. The menu buttons at the top of the page might be a table. You need to get more specific, like “find the table that has ‘COUNTRY NAME’ in the first cell, and get the data from the first cell in each row besides the first.”

You can give a scraper instructions in terms of particular tags, like:

- Find all the

<td>tags - Find the second

<img>tag - Find every

<a>tag that’s inside the third<table> tag

You can also use tag properties, like their IDs and classes, to search more effectively (e.g. “Find every <a> tag with the class external” would match a tag like <a href="http://google.com/" class="external">“).

Regular expressions

Regular expressions are the expert level version of scraping. They are for when the data you want is not neatly contained in a DOM element, and you need to pull out text that matches a specific arbitrary pattern instead. A regular expression is a way of defining that pattern.

Let’s imagine that you had a news article and you wanted to scrape the names of all the people mentioned in the article. Remember, if you were doing this for one article, you could just do it by hand, but if you can figure out how to do it for one article you can do it for a few thousand. Give a scraper a fish…

You could use a regular expression like this and look for matches:

/[A-Z][a-z]+\s[A-Z][a-z]+/

(If you are noticing the way this expression isn’t optimized, stop reading, this primer isn’t for you.)

This pattern looks for matches that have a capital letter followed by some lowercase letters, then a space, then another capital letter followed by lowercase letters. In short, a first and last name. You could point a scraper at a web page with just this regular expression and pull all the names out. Sounds great, right? But wait.

Here are just a few of the false positives you would get, phrases that are not a person’s name but would match this pattern anyway:

- Corpus Christi

- Lockheed Martin

- Christmas Eve

- South Dakota

It would also match a case where a single capitalized word was the second word in a sentence, like “The Giants win the pennant!”

Here are just a few of the false negatives you would get, names that would not match this pattern:

- Sammy Davis, Jr.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Jean-Claude Van Damme

- Ian McKellen

- Bono

- The Artist Formerly Known as Prince

The point here is that figuring out the right instructions for a scraper can be more complicated than it seems at first glance. A scraper is diligent but incredibly stupid, and it will follow all of your instructions to the letter, for better or worse. Most of the work of web scraping consists of the detective work and testing to get these patterns right.

The simpler and more consistent your information is, the easier it will be to scrape. If it appears exactly the same way in every instance, with no variation, it’s scraper-friendly. If you are pulling things out of a simple list, that’s easier than cherry-picking them from a rich visual layout. If you want something like a ZIP code, which is always going be a five-digit number (let’s ignore ZIP+4 for this example), you’re in pretty good shape. If you want something like an address, that mostly sticks to a pattern but can have thousands of tiny variations, you’re screwed.

Exceptions to the rule are a scraper’s nemesis, especially if the variations are minor. If the variations are large you’ll probably notice them, but if they’re tiny you might not. One of the dangers in creating a scraper to turn loose on lots of pages is that you end up looking at a sample of the data and making the rules based on that. You can never be sure that the rest of the data will stick to your assumptions. You might look at the first three pages only to have your data screwed up by an aberration on page 58. As with all data practices, constant testing and spot checking is a must.

AJAX and dynamic data

A basic scraper loads the page like a human being would, but it’s not equipped to interact with the page. If you’ve got a page that loads data in via AJAX, has time delays, or changes what’s on the page using JavaScript based on what you click on and type, that’s harder to scrape. You want the data you’re scraping to all be in the page source code when it’s first loaded.

Data that requires a login

Mimicking a logged in person is more difficult than scraping something public. You need to create a fake cookie, essentially letting the scraper borrow your ID, and some services are pretty sophisticated at detecting these attempts (which is a good thing, because the same method could be used by bad guys).

Data that requires the scraper to explore first

If you want to pull data off a single page, and you know the URL, that’s pretty straightforward. Feed the scraper that URL and off it goes. Much more common, though, is that you are trying to scrape a lot of pages, and you don’t know all the URLs. In that case the scraper needs to pull double duty: it must scout out pages by following links, and it must scrape the data off the results. The easy version is when you have a hundred pages of results and you need to teach your scraper to follow the “Next Page” link and start over. The hard version is when you have to navigate a complex site to find data that’s scattered in different nooks and crannies. In addition to making sure you scrape the right data off the page, you need to make sure you’re on the right page in the first place!

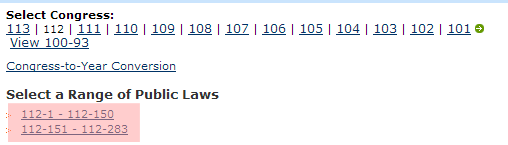

Example 1: THOMAS

Let’s imagine you wanted to scrape the bill number, title, and sponsor of every law passed by the 112th session of the United States Congress. You could visit THOMAS, the official site for Congressional legislative records. It turns out they keep a handy list of Public Laws by session, so that saves you some time. When you click on the 112th Congress, you’ll notice there are links to two pages of results, so you’ll need to scrape both of those URLs and combine the results:

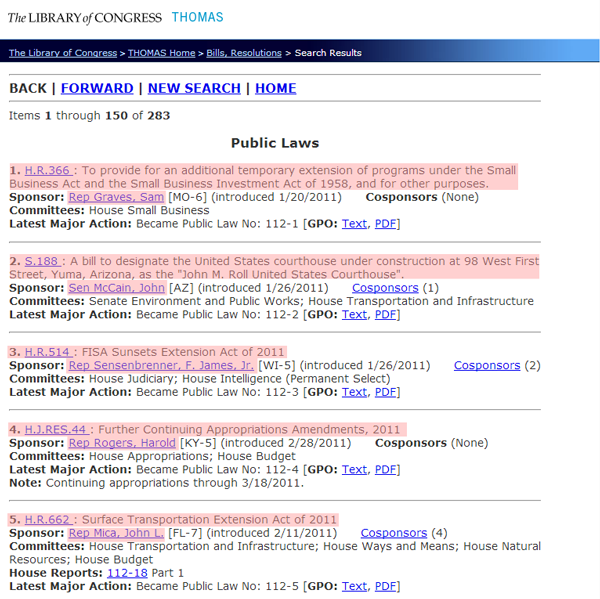

On each page, you get a list of results that displayed the name and sponsor of the law in a seemingly consistent way:

In order to scrape that information and nothing else, we need to put our source code detective hats on (if you’re going to start scraping the web, make sure you get a proper source code detective hat and a film noir detective’s office). This is where it gets messy. That list looks like this.

<p>

<hr/><font size="3"><strong>

BACK | <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/L?d112:./list/bd/d112pl.lst:151[1-283](Public_Laws)[[o]]|TOM:/bss/d112query.html|">FORWARD</a> | <a href="/bss/d112query.html">NEW SEARCH</a>

| <a href="/home/thomas.html">HOME</a>

</strong></font><hr/>

Items <b>1</b> through <b>150</b> of <b>283</b>

<center><h3>Public Laws</h3></center><p><b> 1.</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HR00366:|TOM:/bss/d112query.html|">H.R.366 </a>: To provide for an additional temporary extension of programs under the Small Business Act and the Small Business Investment Act of 1958, and for other purposes.<br /><b>Sponsor:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Rep+Graves++Sam))+01656))">Rep Graves, Sam</a> [MO-6]

(introduced 1/20/2011) <b>Cosponsors</b> (None)

<br /><b>Committees: </b>House Small Business

<br /><b>Latest Major Action:</b> Became Public Law No: 112-1 [<b>GPO:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ1/html/PLAW-112publ1.htm">Text</a>, <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ1/pdf/PLAW-112publ1.pdf">PDF</a>]<hr/>

<p><b> 2.</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:SN00188:|TOM:/bss/d112query.html|">S.188 </a>: A bill to designate the United States courthouse under construction at 98 West First Street, Yuma, Arizona, as the "John M. Roll United States Courthouse".<br /><b>Sponsor:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Sen+McCain++John))+00754))">Sen McCain, John</a> [AZ]

(introduced 1/26/2011) <a href='/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:SN00188:@@@P'>Cosponsors</a> (1)

<br /><b>Committees: </b>Senate Environment and Public Works; House Transportation and Infrastructure

<br /><b>Latest Major Action:</b> Became Public Law No: 112-2 [<b>GPO:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ2/html/PLAW-112publ2.htm">Text</a>, <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ2/pdf/PLAW-112publ2.pdf">PDF</a>]<hr/>

<p><b> 3.</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HR00514:|TOM:/bss/d112query.html|">H.R.514 </a>: FISA Sunsets Extension Act of 2011<br /><b>Sponsor:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Rep+Sensenbrenner++F.+James++Jr.))+01041))">Rep Sensenbrenner, F. James, Jr.</a> [WI-5]

(introduced 1/26/2011) <a href='/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HR00514:@@@P'>Cosponsors</a> (2)

<br /><b>Committees: </b>House Judiciary; House Intelligence (Permanent Select)

<br /><b>Latest Major Action:</b> Became Public Law No: 112-3 [<b>GPO:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ3/html/PLAW-112publ3.htm">Text</a>, <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ3/pdf/PLAW-112publ3.pdf">PDF</a>]<hr/>

<p><b> 4.</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HJ00044:|TOM:/bss/d112query.html|">H.J.RES.44 </a>: Further Continuing Appropriations Amendments, 2011<br /><b>Sponsor:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Rep+Rogers++Harold))+00977))">Rep Rogers, Harold</a> [KY-5]

(introduced 2/28/2011) <b>Cosponsors</b> (None)

<br /><b>Committees: </b>House Appropriations; House Budget

<br /><b>Latest Major Action:</b> Became Public Law No: 112-4 [<b>GPO:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ4/html/PLAW-112publ4.htm">Text</a>, <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ4/pdf/PLAW-112publ4.pdf">PDF</a>]<br /><b>Note: </b>Continuing appropriations through 3/18/2011.

<hr/>

<p><b> 5.</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HR00662:|TOM:/bss/d112query.html|">H.R.662 </a>: Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011<br /><b>Sponsor:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Rep+Mica++John+L.))+00800))">Rep Mica, John L.</a> [FL-7]

(introduced 2/11/2011) <a href='/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HR00662:@@@P'>Cosponsors</a> (4)

<br /><b>Committees: </b>House Transportation and Infrastructure; House Ways and Means; House Natural Resources; House Budget

<br/><b> House Reports: </b>

<a href="/cgi-bin/cpquery/R?cp112:FLD010:@1(hr018)">112-18</a> Part 1<br /><b>Latest Major Action:</b> Became Public Law No: 112-5 [<b>GPO:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ5/html/PLAW-112publ5.htm">Text</a>, <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ5/pdf/PLAW-112publ5.pdf">PDF</a>]<hr/>

What? OK, calm down. There’s a lot going on in there, but we can compare what we see visually on the page with what we see in here and figure out the pattern. You can isolate a single law and see that it follows this pattern:

<p><b> 1.</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d112:HR00366:|TOM:/bss/d112query.html|">H.R.366 </a>: To provide for an additional temporary extension of programs under the Small Business Act and the Small Business Investment Act of 1958, and for other purposes.<br /><b>Sponsor:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Rep+Graves++Sam))+01656))">Rep Graves, Sam</a> [MO-6]

(introduced 1/20/2011) <b>Cosponsors</b> (None)

<br /><b>Committees: </b>House Small Business

<br /><b>Latest Major Action:</b> Became Public Law No: 112-1 [<b>GPO:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ1/html/PLAW-112publ1.htm">Text</a>, <a href="/cgi-bin/toGPObsspubliclaws/http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-112publ1/pdf/PLAW-112publ1.pdf">PDF</a>]<hr/>

The bill number is located inside a link:

<a href="...">H.R.366 </a>

But we can’t treat every link as a bill number, there are other links too. This link comes after two <b> tags, so maybe we can use that, but that would also match some other links, like:

<b>GPO:</b> <a href="...">Text</a>

So we need to get more specific. We could, for example, specify that we want each link that comes after a numeral and a period between two <b> tags:

<b> 1.</b><a href="...">H.R.366 </a>

There’s more than one way to skin this particular cat, which is nothing unusual when it comes to scraping.

We can get the sponsor’s name by looking for every link that comes immediately after <b>Sponsor:</b> and getting the text of that link.

<b>Sponsor:</b> <a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Rep+Graves++Sam))+01656))">Rep Graves, Sam</a>

leads us to

<a href="/cgi-bin/bdquery/?&Db=d112&[email protected]([email protected]((@1(Rep+Graves++Sam))+01656))">Rep Graves, Sam</a>

which leads us to

Rep Graves, Sam

We need to consider special cases. Can a bill have more than one sponsor? Can it have no sponsors? We also need to make sure we parse that name properly. Does every sponsor start with “Rep”? No, some of them are senators and start with “Sen”. Are there any other weird abbreviations? Maybe non-voting delegates from Guam can still sponsor bills and are listed as “Del”, or something like that. We want to spot check as much of the list as possible to test this assumption. We also want to investigate whether a sponsor’s name could have commas in it before we assume we can split it into first and last name by splitting it at the comma. If we scroll down just a little bit on that first page of results, we’ll find the dreaded exception to the rule:

Sen Rockefeller, John D., IV

Now we know that if we split on the first comma, we’d save his name as “John D., IV Rockefeller,” and if we split on the last comma, we’d save his name as “IV Rockefeller, John D.” Instead we need something more complicated like: split the name by all the commas. The first section is the last name, the second section is the first name, and if there are more than two sections, those are added to the end, so we get the correct “John D. Rockefeller IV.”

Example 2: sports teams, stadiums, and colors

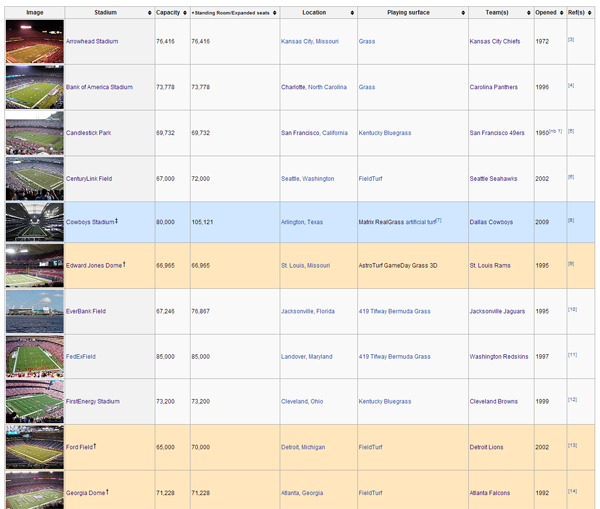

Let’s say you wanted to get the list of all NFL football teams with their stadiums, stadium locations, and team colors. Wikipedia has most of this information available in some form or another. You could start here and you’d find this table:

This seems pretty straightforward. The second column is the stadium name, the fifth column is the location, and the seventh column is the team, so that gets us 3 out of the 4 data points we want.

But of course it’s not that simple. Wikipedia sometimes includes annotations in the text, and we want to make sure we don’t include those as part of what we scrape. Then, if you scroll down to MetLife Stadium, you find the dreaded exception to the rule. It has two teams, the Giants and Jets. We need to save this row twice, once for each team.

Let’s imagine we wanted a more specific location than the city. We could do this by having our scraper follow the link in the “Stadium” column for each row. On each stadium’s page, we’d find something like this:

We could save that and we’d have a precise latitude/longitude for each stadium.

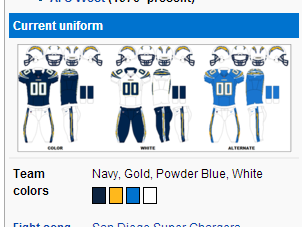

In the same fashion, we can get the team colors by following the link to each team in the “Team(s)” column. We’d find something like this:

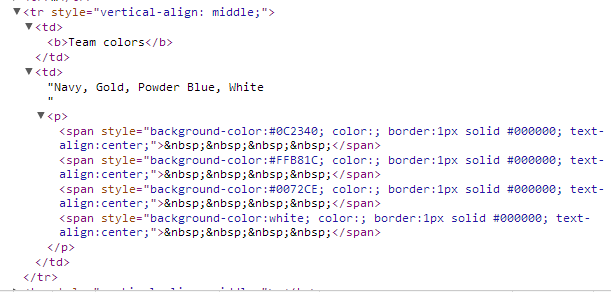

If we inspect those elements, we’d find something like this:

That “background-color” is what we want, and there’s one for each color swatch on the page. So we could say something like “Find the table cell that says ‘Team colors’ inside it, then go to the next cell and get the background color of every <span> inside a pair of <p> tags.”

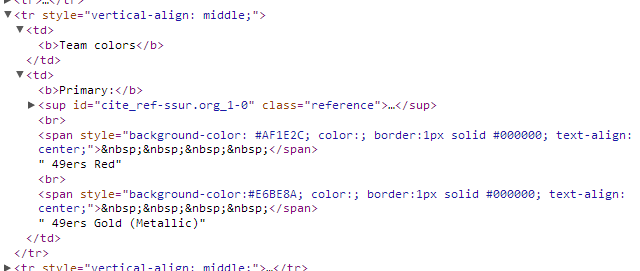

You’ll notice that three of them are special color codes (“#0C2340″,”#FFB81C”,”#0072CE”) and one is plain English (“white”), so we need to keep that in mind, possibly converting “white” into a special color code so they all match. As usual, we need to be skeptical of the assumption that every page will follow the same format as this one. If you look at the San Francisco 49ers page, you’ll see that the way the colors are displayed varies slightly:

The rule we wrote before turns out to be overly specific. These <span> tags aren’t inside of <p> tags. Instead, we need to broaden our rule to get the background-color of any <span> in that cell.

ScraperWiki: Your web scraping sandbox

If you want to write your own scrapers, there’s no way around writing some code. A scraper is nothing but code. If you’re a beginner, though, you can check out ScraperWiki, a tool for writing simple web scrapers without a lot of the hassle of setting up your own server. The best thing about ScraperWiki is that you can browse existing scrapers other people have written, which will help you learn how scraper code works, but also give you the opportunity to clone and modify an existing scraper for a new purpose instead of writing one from scratch. For instance, this is a basic Twitter search scraper:

https://scraperwiki.com/scrapers/ddj_twitter_scraper_9/

By just changing the value of QUERY, you have your own custom Twitter scraper that will save tweets that match that search and give you a table view of them.

This scraper saves Globe and Mail headlines:

https://scraperwiki.com/scrapers/bbc_headlines_8/

If you add an extra line to filter them, you can start saving all Globe and Mail headlines that match a particular keyword.

Leave a Reply