Hark, do you hear that? There be dragons in them hills surrounding Lake Orta just north of Milan, Italy. Or maybe it’s the collective roar of all 134 attendees of Tactical Technology Collective’s 2013 Info-Activism Camp: Evidence & Influence, a week long peer-learning conference attended by activists, designers and technologists from 46 countries.

But wait, maybe it is dragons. Yes, definitely dragons. Dangerous dubious data dragons deluging and daunting camp attendees. How can we slay such beasts?

With a Data Expedition, naturally! (Forewarning for our readers, there was bloodshed.)

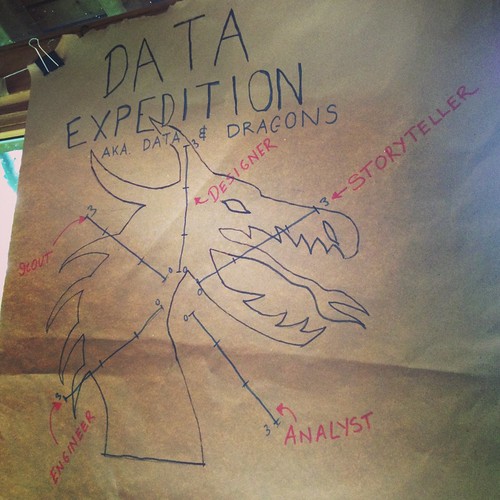

On the 5th day of camp, Lucy Chambers from School of Data, Juan Casanueva from Escuela de Datos, Max Richman representing DataKind, and Murray Hunter, a South African freedom of information campaigner, collaboratively led a data expedition at TTC Camp. What is a Data Expedition, you ask?

Much like mountaineering, data investigations are better done as teams, you’ll need a mix of skills from engineer to storytellers, including designers, scouts and analysts in your mix – you may need a sherpa to negotiate the tricky bits and keep pushing you when the chocolate runs out. Much like mountaineering, in a data investigation, you can often see the peak, you know where you want to get to (or which dragons you want to slay), but the route there is not always obvious, some paths will be blocked and you will have to find another way to the top. Data expeditions are sherpa-ed shared-brain problem-solving exercises – where a team assembles to tackle a real-life problem through using data…

The Key Point Problem – Information Asymmetry

So which dragons did we aim to slay? We took on an issue put on the table by the Right2Know campaign, an access-to-information group in South Africa. Using a 30-year-old national security law, the government of South Africa has designated a large number sites around the country (400+) as National Key Points where protests or public gatherings are not allowed. Not only are these locations unknown, but so are their criteria for designation and none of this information can be acquired by a freedom of information request. In short, the government will not provide a comprehensive list of these locations (where they are) and explanation for how they are determined (what they are).

So we fifteen-odd participants set our sights on this two-headed dragon.

In case you are wondering, it turns out you can slay a dragon from the flat of your back…

Leaving basecamp

After introducing the issues, participants completed character sheets to identifying data expedition roles. In our ranks we had a number of scouts and storytellers, as well as a few designers, analysts and engineers littered around the room. We then split-up into two balanced teams. One team set to focus on the “where” of the National Key Points and the other on the “what.”

Our expedition would step through four phases of dragon abatement: 1) Hunt 2) Clean 3) Study 4) Show.

During steps 1 and 2, many of the ideas for hunting the data included scraping government data sources such as parliamentary notes and police records of protests denied or permitted. The teams identified a range of new sources that Murray plans to further pursue back in South Africa.

For steps 3 and 4, much like popular cooking shows on television, there was a “one I made earlier” partially cooked version of the data ready to work with. Murray already had made some progress on scavenging various data sources so he then shared his hundred locations for the group to further explore and display.

With this data, one group (researching the “what” question) added additional columns for verification status and tagged each key point based on being public, private, utility and/or infrastructure in order to allow the analysis to take place. After tagging, analysis of the coding indicated that most sites were government infrastructure, but a few raised eyebrows by not having any particular obvious sensitivity.

The second group launched straight into the topic of “where”, helping Murray to identify a couple of low hanging fruit in places that he hadn’t thought of looking before for data. We won’t spoil Murray’s fun in disclosing yet what these are until he’s had a chance to try them out, but hope he’ll keep us posted!

The Bloodshed

Murray, so impassioned by the findings from the expedition and progress towards slaying of the two-headed dragon, began to bleed from the nose as he summarized the days learning.

A couple of tips for data hunters

In the section below, Murray highlights what impact the Data Expedition had on his project, and gives tips for others, embarking on a similar quest.

Come with a data problem:

This may seem like an obvious one to veterans of the data expedition model, but many of us have been to hackathons where loads of interesting, smart people show up, there’s oodles of talent and energy in the room, but no clear data problem. Too often we end up wasting valuable time trying to generate a data problem – and if you’re lucky enough to find one, there’s less time to spend solving it. If you come with an existing data problem, not only does it mean that the group has the certainty that their efforts will advance a ‘live’ issue that people are already working on, but it means the expedition can get straight down to the business of generating solutions.

Come with a dataset (or as much of one as you can find):

It was a useful exercise in its own right to begin building the dataset, but it was useful to pull out the half-complete, premade dataset once people’s creative juices were flowing. Building datasets can be so time consuming that sometimes it takes days, not hours – so a premade data set (even if it’s only halfway done) means you can make more efficient use of the expeditioners’ time and talents.

Hivemind knows best:

Says Murray:

“My campaign has been working on the National Key Points Act for over a year, and some of the people in my team have been working on it for more than a decade. In this session, people who’d never even heard of the National Key Points broke new ground within 20 minutes. More brains = more solutions.”

Has your NGO hit a data obstacle? Interested in running a data expedition with your own project to see if you can overcome it? Get in touch!

]]>